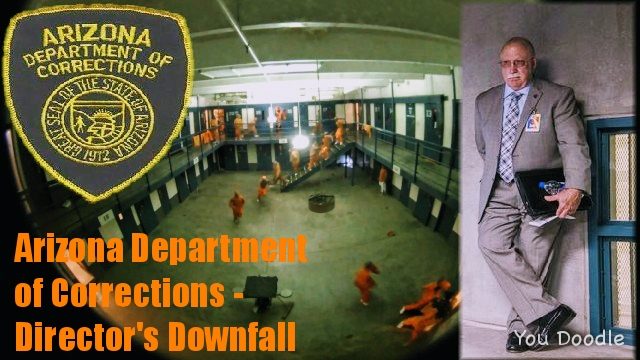

Corruption, Lies, Misdeeds: Arizona Department of Corrections

Has Arizona Governor Doug Ducey finally begun to drain his own swamp? Embattled Director Charles Ryan resigned from the Arizona Department of Corrections on September

Has Arizona Governor Doug Ducey finally begun to drain his own swamp? Embattled Director Charles Ryan resigned from the Arizona Department of Corrections on September

Deputy Guzman in his own words, On March 31, 2019, I arrived to work and grabbed all my paperwork for my overtime post

The employees of the Arizona Department of Corrections are emerging from the shadows. They are unafraid, and are coming forward to share their stories of

By Frank Drebin What has happened to the corrections system in Arizona? It seems to have shifted its focus from punishment to rehabilitation. Rehabilitation and